Two decades after his death, Richard Guadagno’s memory is scattered through his sister Lori’s house.

The guitars he made by hand. His brown North Face jacket from the Department of Fish and Wildlife. “I still wear his clothes. I swear,” Lori said. “I have his ripped up Levis. I have, I have his bike, whatever I can do to kind of bring [Rich] back.”

Lori’s story is a story about a deep wound that has never healed.

It’s also a story about everyday items — a badge; a bird’s nest; a wallet; rolls of film; some tomatoes — that, to Lori, have continued a conversation between her and someone she was closer to than anyone else on Earth.

Tim Lambert / WITF

Lori Guadagno keeps her brother’s memory alive with his objects scattered throughout her home.

“We share the same DNA”

Richard Guadagno was a quiet, intense kid. He loved nature.

When his dad took him golfing and sent him into the woods and streams alongside the course to gather stray golfballs, Rich would return with tadpoles.

He trailed the old Italian men in his New Jersey neighborhood as they grew backyard tomatoes, watching and learning their techniques.

He especially loved frogs.

“We were at a seafood restaurant on the Jersey Shore,” Lori recalled. “Rich saw on the menu that they served frog legs and he lost his mind. We couldn’t eat there. He was hysterical.”

That love of nature remained as Rich became an adult. He built a career at the Department of Fish and Wildlife, eventually becoming a manager at a preserve in northern California.

That intensity remained, too.

Tim Lambert / WITF

Lori says she still wears Rich’s Department of Fish and Wildlife jacket.

“I mean, he was not a big guy, but he could bench press 300 pounds. He was fit. And he took that very seriously,” Lori said. “Like, he would run seven miles at night. I’d be on the couch, eating chips.”

“Lori and Richard were more than brother/sister. They were extremely close, extremely close,” their father, Jerry, told the National Park Service in a 2006 oral history interview.

Their relationship grew even tighter as adults, when both of them ended up on the West Coast. As Lori put it, “There’s no one on this planet that can understand who we are, where we came from. You know, we share the same DNA.”

They had been together right before 9/11. Lori had recently moved back east, to Vermont.

Rich flew out to visit her there, and they drove south together to New Jersey to celebrate their grandmother’s 100th birthday. The party hall was crawling with extended family — cousins, second cousins and honorary uncles and aunts all over.

It was Sept. 8, 2001.

Lori remembers several things from that day: Rich, ever the intense introvert, stalking the party hall, snapping roll after roll of film on his 35 millimeter camera. She remembers him loosening up late in the party, when someone handed him his very first Martini.

Mostly, Lori remembers the end of the night. The two of them arrived back at the home they grew up in.

Photos of Rich and Lori around 2001.”And then both of us looked at each other in my mom’s kitchen. And at the same time, we knew that there was a serious piece of eggplant Parmesan in the refrigerator, leftover from a previous meal. We both wanted it. And so he jumped on my back as we fought in the kitchen for this coveted piece of eggplant, because that’s the kind of siblings we were.”

“We suddenly resorted to being 8 and 6,” she said.

Lori left early the next day for the long trip back up to Vermont.

“One thing about us, ever since we were kids, is we sucked at goodbyes,” said Lori. “We were really sentimental with goodbyes, like two fools.”

Her last glimpse of her younger brother was him standing in the window watching her drive away.

They talked one more time, late that night when Lori had arrived back in Vermont. Rich told her he had double checked the ticket for his flight back to California. He told her he was glad he had looked, because he had forgotten what day he was supposed to head back.

He was booked on United Flight 93. On Tuesday, Sept. 11.

Two days later, Rich was gone and Lori found herself again heading south, retracing the same drive. Pulling up to the same house, and looking into the same window where her brother stood just days before.

“When I drove up, there were all of these cars in front of my house, and I just knew everything had changed. Everything,” Lori said. “The world had changed, but my family had changed, too.”

The badge

Everything was a blur those first two months. More than anything else, Lori just felt angry.

“I really wanted to be alone. I wanted to remain isolated,” she said. “It was not a pretty side of me. I’m not proud of it at all, but I’m just being honest.”

In late October, an FBI agent named Ed Ryan reached out with a startling update.

Ryan was one of the investigators at the Pentagon, and on his first off day in more than a month, had felt compelled to ride out to Shanksville on his motorcycle. He walked down to the crash site and back into the woods, where debris from Flight 93 had scattered throughout the grove of hemlocks when the plane smashed into the ground at 563 miles per hour.

Something caught Ryan’s eye as he looked into the woods.

Lori has kept a printout of the email, dated Oct. 20, 2001, that Ryan sent to an official at the Department of Fish and Wildlife, who got it to the Guadagno family. It reads like an FBI field report.

Tim Lambert / WITF

A leather case that housed Rich’s credentials from the Fish and Wildlife department was found in October 2002.

“I saw what appeared to me to be a credential case. They were laying on the ground, face up and open,” he wrote.

The leather case law enforcement — like FBI agents or fish and wildlife officers — keep their badges in. There was a security fence between Ryan and the badge, but he got someone inside it to go take a look.

It was Rich’s badge.

“Obviously, I never knew Richard, but I’m sure that we have some things in common. My guess is that he’d probably like to see his [credentials] end up where they belong: with his family,” Ryan wrote.

When Flight 93 smashed into the ground, upside down and at a 40-degree angle, the cockpit and first class section broke off and skipped into the hemlock trees.

The fact the badge was found in the trees — and not the big crater in the open field where most of the rest of the flight’s debris had ended up — told Lori and her family something important: At the time of impact, Richard was most likely up in the front of the plane, in or near the cockpit.

That meant he had almost certainly been one of the passengers who had fought back against the terrorists to keep the plane from striking another target –likely, investigators later determined, the U.S. Capitol.

Lori and her family had never really doubted it. Rich, after all, was the intense fitness freak who was always cool in a crisis, and he had a deep, engrained sense of right and wrong.

But unlike the others who tried to take back the plane, he never made a cell phone or Airfone call from the doomed flight. That meant he wasn’t one of the celebrated heroes in the early weeks after 9/11.

“I think it was something we already knew,” she said, after re-reading that email nearly 20 years after it was first sent. “But it was that little extra piece that just confirmed it.”

The bird’s nest

The next object came about a year later, on the anniversary of 9/11. It was Lori’s first visit to the crash site in Shanksville.

In the early months after the attacks, Lori’s parents had gone there and gotten to know other families who lost people on Flight 93.

But when Lori thought of that site, she thought of what she had seen on TV that day: the burning trees, the ugly gash in the ground. It seemed wrong to her that the nature Richard loved was so ugly.

“And so I didn’t want to go there,” Lori said. “I didn’t want to be present in all of the devastation that was there, that I was seeing bits and pieces of. I can understand why a lot of family members were drawn to it and want it to be there immediately. But I wanted nothing to do with it.”

Still, as the first anniversary of the crash neared, Lori knew she’d have to go to Shanksville to support her parents.

The first anniversary was cold and windy. The flags lining the fences around the crash site whipped in the wind.

The Red Cross handed out blankets to the attendees, but quickly ran out.

Johnstown’s orchestra, joined by U.S. Marine Corps musicians, played Aaron Copeland. Family members and public officials spoke. A friar rang a large bell after the name of every person on Flight 93 was read.

None of it moved Lori.

She glowered during the ceremony, cringed at the way her grief was on public display. She was icy toward other relatives of passengers and crew, by her own admission.

When it was over, the families and friends made their way slowly to the crash site.

The field, burned by the plane’s impact and the intense heat of the jet fuel fires, was now filled with green grass — except around where the gaping crater once was.

In that field, Lori wandered off by herself.

“I remember looking up to the sky, really pissed off. I said, ‘Rich, if you can hear me, just show me a sign. I need to know you know I’m here. I need to feel you here,'” Lori recalled.

She took one more step into the field and looked down. She saw a perfectly-formed bird’s nest, made of mud and twigs.

Tim Lambert / WITF

Lori holds a bird’s nest.

“If I took a step that was two inches further, I would have crushed it,” Lori said. “So I picked up this nest, and I am running in the field with the nest screaming, ‘Mom! Dad! Mom, Dad, where are you? It’s Rich, it’s Rich!'”

As Lori remembers it two decades later, she conceded her parents might have thought she’d lost it.

But she explained to them that she had asked for a sign from her brother who loved nature, who hunted for tadpoles as a kid and then devoted his adult life to protecting it. And there, to her, it was.

Lori kept that nest, cradled it in her arms. She flew home with it protected on her lap. And two decades later, it’s still there in her house, under a glass protective case.

She had gone to that ceremony angry at the land that had swallowed up her brother’s plane. She still left angry — but once she found that bird’s nest, “some little part of my heart started cracking a bit.”

The wallet

Not every item brought Lori Guadagno solace, though.

“This — this was not an easy thing to receive. Clearly,” she said, as she opened a box next to the bird’s nest.

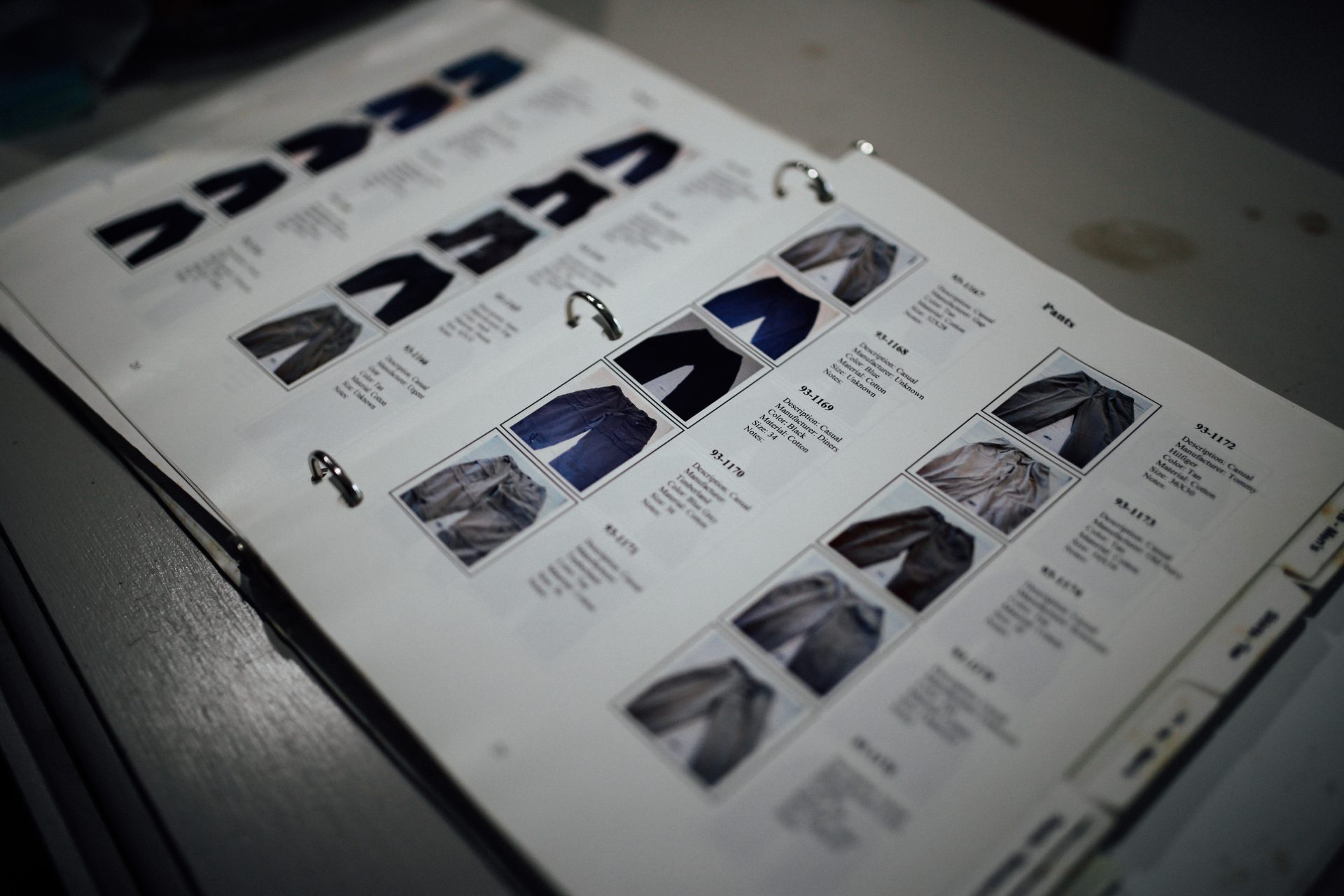

It held a white three-ring binder. The cover read: “Unassociated Personal Effects of Flight 93.” It arrived at Lori’s house in 2002.

Tim Lambert / WITF

Family members received a binder of catalogued clothes and personal objects that were found at the crash site. Lori went through it to see if she could identify anything that belonged to her brother.

“All the family members receive this to go through for all of the unclaimed unidentified personal effects that were gathered from the flight,” she explained. “So, unfortunately, we all had to go through — page by painstakingly horrible page — to see if we could identify articles.”

The table of contents was a mundane list of things any of us would pack on a trip. Bathing suits, hair bands, belts, bags, dresses, hats, and pants each have their own section.

Women’s shirts. Men’s shirts.

Pairs of shoes and individual shoes were catalogued separately.

The binder is filled with photographs of these items. They’re all laid out on tables, with accompanying text describing their characteristics.

It was so clinical — and yet for Lori, it couldn’t get any more personal.

“Because then it felt like, as someone was looking at Richard’s personal items, I was looking at theirs. This just felt, almost like a violation. Yet absolutely necessary,” she said.

“I went through every, every single page. Because the thing is, I knew what my brother was wearing. I knew what was in his suitcase. So I was ready — I was so ready to look at these items and say, there it is. There’s his Pearl Jam disc. There’s his running shorts. There are his sneakers.”

Tim Lambert / WITF

Rich’s hemp wallet was the only thing Lori could id from the binder. It still held a receipt from their time together in Vermont.

The only thing she could identify was a hemp wallet Rich had bought during that visit to Vermont, just before the big birthday party for their grandmother. It still had receipts inside, including from a meal he and Lori had shared. The material had soaked up the smell of the plane’s jet fuel.

For hours, Lori pulled out various items from Rich. All day, it had been clear how much everything meant to her.

This was different. Her voice shook. She sounded uncertain.

“Now, these are things that I tuck away and I don’t really ever look at or touch,” Lori explained. “I know they’re there. I need to know they’re there — but just last night, gathering these things, it’s so much harder,” she said, pausing. “20 years.”

“The pain never goes away,” she continued. “Obviously I’ve never had closure in this story. I never will. But I found a place to put it so that I can lead a happy, productive life.

“And I know that’s what Rich would want. But when I touch these relics, It’s — it’s — this is really tough — tough shit.”

The film

There’s one other thing Lori wants to show us.

It didn’t arrive until about ten years after 9/11.

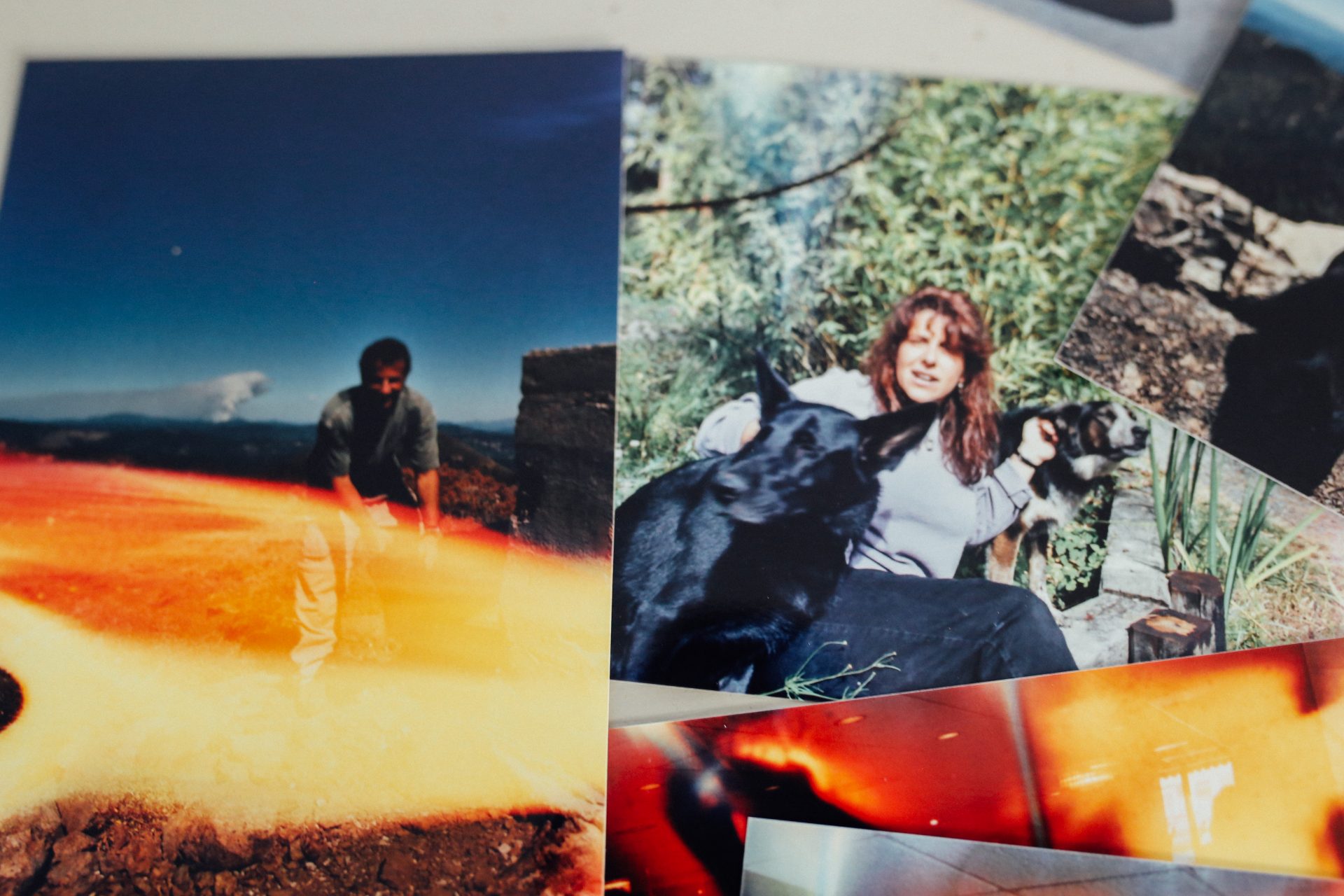

Tim Lambert / WITF

Rolls of film taken by Rich were found by the FBI.

She got a call from the FBI. They had more personal items that had been held back as potential evidence, but were ready to be released.

“And one of the things in this message [was] ‘photographs of a 100th birthday party,'” Lori told us.

The family gathering the weekend before 9/11. The rolls of film Rich methodically shot. Lori had hoped they would show up in that terrible binder, but she had accepted that they were gone forever.

The FBI had developed the film in August 2010. The photographs were licked with the flames of the plane crash. Ghostly burn marks bubble through them.

But there’s Lori’s family, three days away from their lives changing forever.

Lori says it was haunting to get those photographs nearly a decade later. “And yet it was like this gift too,” she said. “Because it was other pieces of him that came back to us.It was ghostly and sublime at the same time, and a gift for sure.”

A happy family. All together on Sept. 8, 2001.

Tim Lambert / WITF

In 2010, the FBI developed Rich’s photos from their grandmother’s birthday party.

“I see these pictures. I see this party. I see these tidbits and relics marking that time. And I know so shortly after everything changed for my family,” she said, flipping through the damaged images.

The tomatoes

Lori Guadagno has spent 20 years now living in this changed world.

For her, these objects — the badge, the film, the bird’s nest, everything else — they keep Rich’s memory alive.

There’s one final object that turned up earlier this summer when we went to talk to Lori in Jacksonville Beach, Fla.

It was about 45 minutes into the interview. We hadn’t gotten to 9/11 itself, and it was clear everyone was dreading making that shift.

We had talked about Rich and Lori’s close relationship. About his love of nature. About his lifelong obsession with growing tomatoes, going back to those days watching the old men in the neighborhood grow them. When Lori had visited Rich in California in the summer of 2001, his property was filled with tomato vines.

The conversation inched forward, into late August 2001, then September. The 100th birthday party.

“This is the part of the interview where I want to say, ‘and then everything was fine!'” Scott joked.

Finally, we all took a deep breath and began walking through Lori’s 9/11 story.

Then the doorbell rang.

It was a neighbor, who wanted to know if Lori wanted something he had just picked from his garden.

Bright yellow cherry tomatoes.

Tim Lambert / WITF

A neighbor delivered yellow cheery tomatoes from his garden to Lori. She saw it as a sign from Rich since his home in California was filled with tomato vines.

No one said anything. Lori just stared at the tomatoes.

“You know, I always say that the signs that I get from Rich are most peculiar. But they are so crystal clear, and that would be one of them,” she said.

“The hardest part of the conversation — and the tomatoes arrived.”

“OK. Alright, Rich,” Lori finally said, after another long pause. “I’m here to tell your story. I am here to tell your story.”

And she did.

0 Commentaires